By Jacqueline Engel

Words spoken by (the princess Kiya), justified.

“I will breathe the sweet breath which comes forth from your lips, I will behold your beauty every day. My prayer is to hear your voice, sweet like the north breeze.

Your limbs will be young in life, through my love of you, and you will give me your arms which bear your spirit.

I will receive it, and live through it .

You will call out my name for eternity, and it will never fail on your lips.

My lord (Akhenaten], you abide for ever and ever, alive like the Aten.

King of Upper and Lower Egypt who lives upon truth, lord of the Two Lands, the beautiful child of the living Aten who is here, alive for ever and ever.”

The inscription at the foot of the coffin is one originally appropriate for a woman, but later changed to refer to a man. We now suspect that the original subject is Kiya. The inscription is unique both for its poetic imagery and for the light it sheds on Akhenaten’s religion.

Princess Kiya is a shadowy figure, whose life has been pieced together from fragments of inscriptions, some of which were erased by her contemporaries. She is now believed to be the subject of some of the inscriptions found in the most mysterious of royal tombs, number 55 in the Valley of the Kings.

We encounter her only through her husband, Akhenaten, often referred to as ‘the heretic king’.

He came to the throne as Amenophis IV, but broke with established religion and devoted himself to a single deity known as the Aten. He was married to the beautiful Nefertiti. On many of their monuments Akhenaten and Nefertiti are accompanied by their daughters. It appears that the pair had no sons.

There are, however, two spare princes who appear in the records from Amarna, the capital city that Akhenaten founded for himself. These are Smenkhkare and Tutankhaten (the latter means ‘Living image of the Aten’). They are brothers, and the likelihood is that their father is Akhenaten.

Egyptologists are coming to the conclusion that Kiya was the mother of these princes, and it is to this that she owed her influence with the king. Pharaohs were allowed several wives, and Nefertiti may have accepted this, but the situation has the potential to turn nasty. Somebody is responsible for the erasure of Kiya’s names from most of her inscriptions, but we do not know who this is. Kiya died before Akhenaten.

When Akhenaten did die, he was succeeded briefly by Smenkhkare, and then by his second son, who changed his name to Tutankhamun. The discovery of the latter’s tomb in 1922 made him famous, but the fate of Smenkhkare is more obscure.

Tomb 55 in the Valley of the Kings contained objects from the Amarna court, among them a damaged coffin designed for a woman, although the badly preserved body inside this turned out to be male. This may be Akhenaten, but it is more likely that the body is that of Smenkhkare.

Text by John Ray

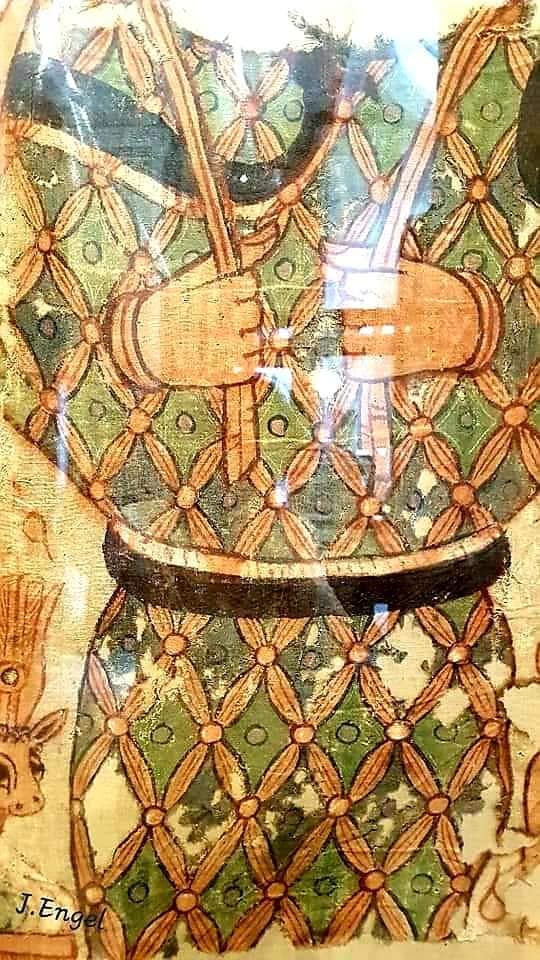

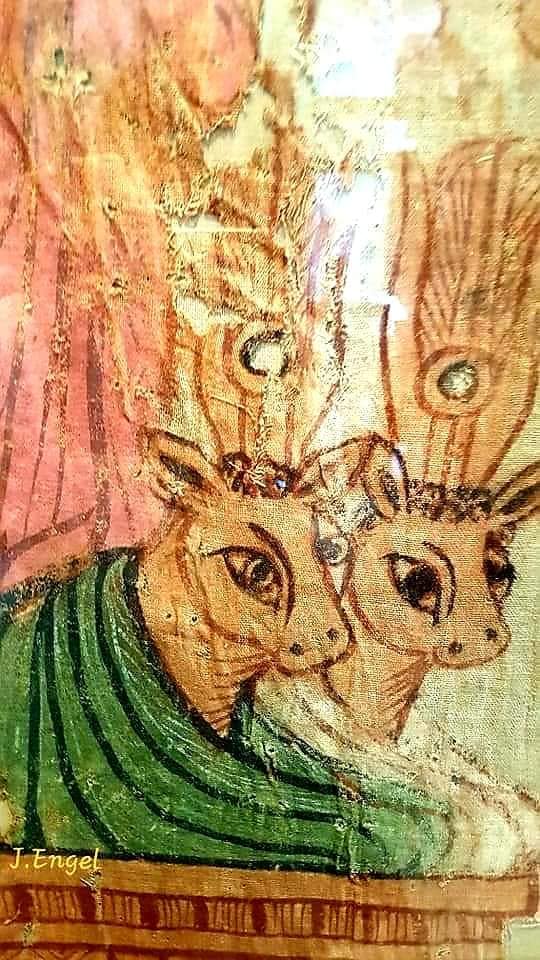

Close-up of what is believed to be one of the Princess Kiya’s canopic jars (a sacred vessel containing one of her preserved vital organs).

Three of the four lids of the Canopic jars belonging probably to Princess Kiya.

(The forth is at the Met)

Egyptian Museum Cairo